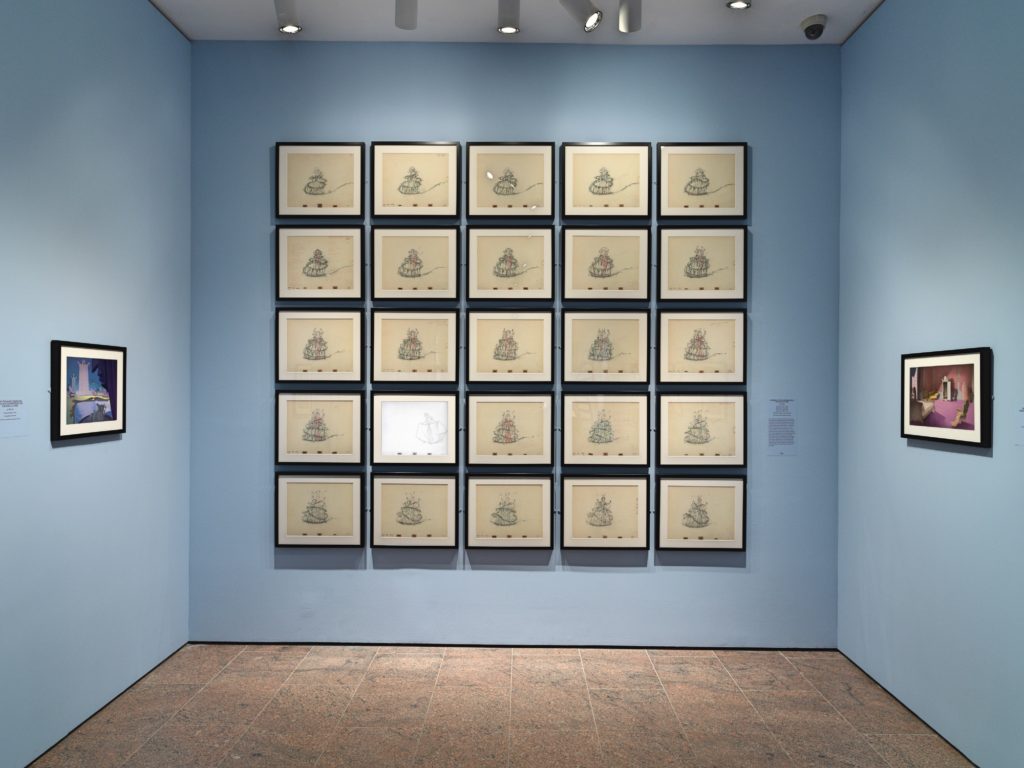

There are a number of exhibits that will be of interest at the recently opened “Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, but the one that will take visitors’ breath away is a series of 25 line drawings drawn by Marc Davis (one is a video) of the transformation of Cinderella’s torn dress into a beautiful ball gown from the 1950 movie of the same name.

The sequence of drawings is simply spectacular and drew gasps from the crowd as they lingered admiring the work of Marc Davis, character animator for the scene and George Rowley, effects animator for the original scene.

“The artifacts that you see on that wall are actually composited reproductions of clean-up animation drawings from sequence 3, scene 41 of Cinderella (1950),” said Fox Carney, Manager, Research, Walt Disney Animation Research Library. “The character level drawings and the sparkle drawings were combined digitally to present both levels together in line art form. In this way, guests could get a sense, at a glance, of the traditional hand-drawn nature of the scene and how intricate such a scene can be – without having to overlay the drawings on top of each other or trying to backlight them.”

Although this imagery has been displayed in the past, Disney has not displayed the material in this volume or in this arrangement. “We may have had 15 or 16 composited reproductions displayed previously,” said Carney. “We have exhibited and/or displayed elements of this scene previously and have shared the movie file of the reconstructed pencil test of that same character and effects levels for the scene.”

This scene, when the Fairy Godmother transforms Cinderella into a princess, was Walt Disney’s favorite piece of animation ever.

The exhibit, which runs through March 6th, 2022 before traveling to London, is the first-ever exhibition at The Met to explore the work of Walt Disney and the hand-drawn animation of the Walt Disney Animation Studios. According to the press release, the exhibit will “draw new parallels between the magical creations of the Disney Studios and their artistic models, examining Walt Disney’s personal fascination with European art and the use of French motifs in Disney films and theme parks.”

An audio guide is available for the exhibit. Guests can access it for free through The Met’s website or on Spotify and listen to it on a mobile device. They can also rent an audio guide at the museum. The description of each item is narrated by Paige O’Hara, the voice of Belle from Beauty and the Beast, with guest voice work from Angela Lansbury, Mrs. Potts. Interviews with Wolf Burchard – Exhibition Curator, Associate Curator in The Met’s Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts are included as well, in addition to Glen Keane – Disney animator who developed characters for The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Tarzan, Don Hahn – producer of animated films, including The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast, and Jean Gillmore – Disney artist specializing in the development of characters and their costumes for animated films.

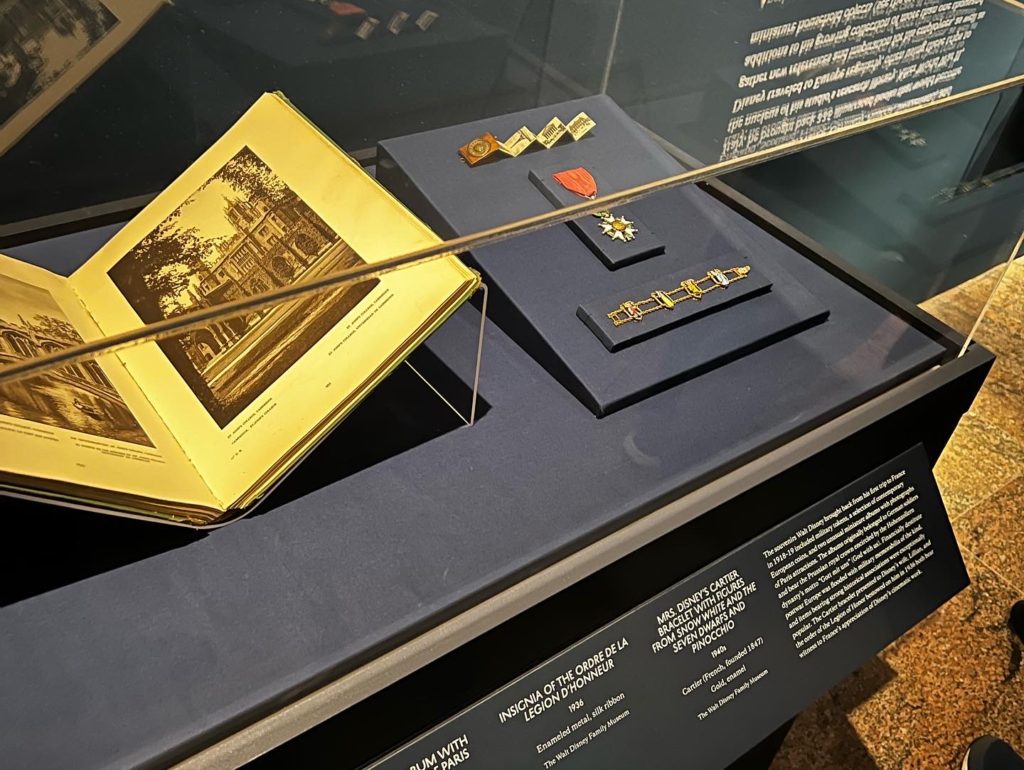

Organized thematically and covering decades of Disney animation, the exhibit starts with Walt’s relationship with France and his encounters with European art and architecture. He had a passion for collecting and building miniature furniture and dollhouse contents. There is a selection of these objects on display along with Walt’s Insignia of the Ordre de la Legion D’Honneur, a Cartier bracelet with figures from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio worn by Lillian Disney, as well personal film footage of Walt and his family visiting Paris and Versailles.

The remainder of the exhibits mix objects, drawings, paintings, and other ephemera from the Walt Disney Studios along with porcelain, furniture, and other decorative arts throughout the centuries. According to the press notes, in the “Animating the Inanimate” there is “a presentation of French and German Rococo porcelain figurines alongside story sketches for two of Disney’s Silly Symphonies: The Clock Store (1931) and The China Shop (1934). These types of whimsical porcelain figures, originally inspired by the pastoral scenes of French Rococo painter Antoine Watteau and his contemporaries, were brought to life by the first generation of Disney animators. Connections will be made between the remarkable technological advancements of the Meissen and Sèvres porcelain manufactories over the course of the 18th century and the cinematic innovations pioneered by Disney animators at the beginning of the 20th.”

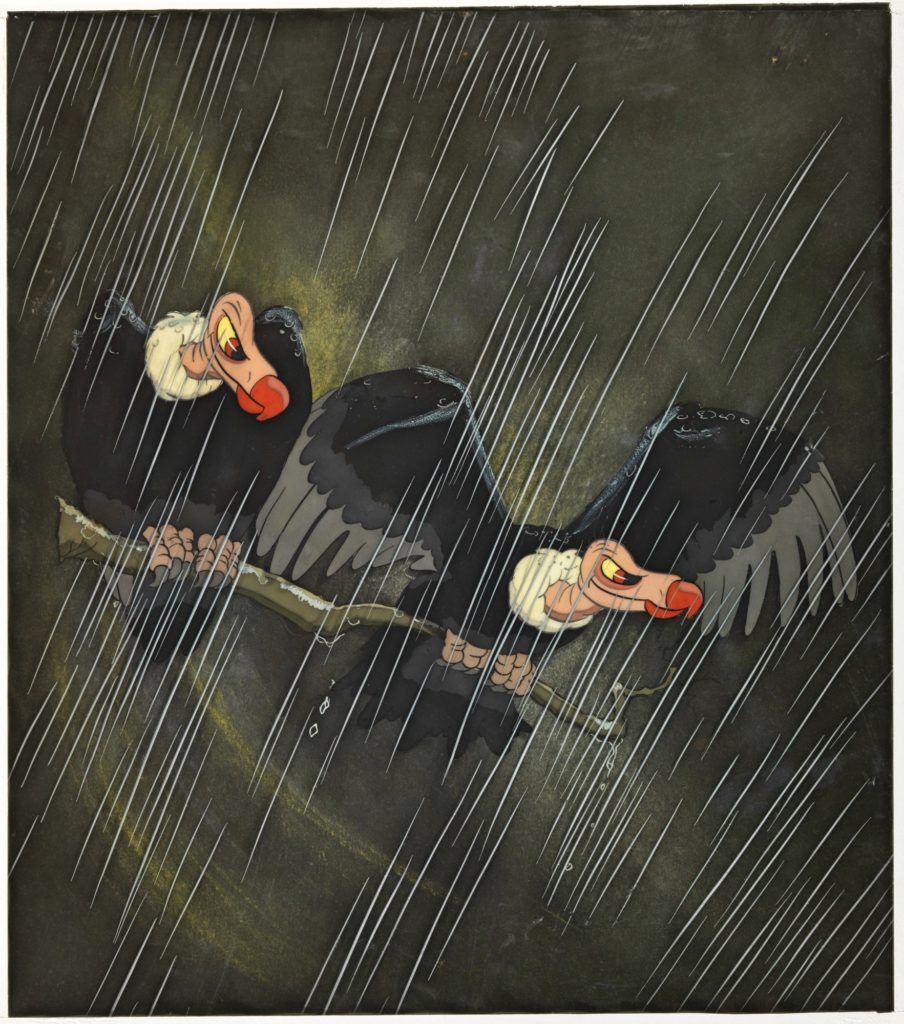

The next couple of sections focus on three early animated features, beginning with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Included is a gouache on celluloid depicting two avid-eyed vultures from the film, which Walt Disney presented to The Met in 1938. When he donated the cell to the Museum, a February 26, 1939 article in The New York Times Magazine asked, “It’s Disney, but is it art?” (This is also the title of one of the exhibit’s sections).

The New York Times Magazine interviewer stated, “No, Disney doesn’t know anything about art. Today, he is the world’s greatest single employer of artists: there are 600 of them on his payroll.”

“The distinctly Germanic atmosphere of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs contrasts with the Francophile look of Cinderella (1950) and Sleeping Beauty (1959), both adapted from the original tales written at the dawn of the 18th century by Charles Perrault, the influential man of letters at the court of Louis XIV. The Cinderella section spotlights the barrier-breaking female artists who entered the creative realm of the Disney Studios, including Bianca Majolie and Mary Blair.

In addition to art from the Disney Studios, there are two pieces from the Walt Disney Archives. Both are elaborate book props from the opening scenes of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Cinderella.

Blair is one of the most famous of Disney’s female artists and was not only responsible for the distinctive looks of the studios’ feature films from the 1940s and early ’50s but the decor that defines Disney’s Contemporary Resort hotel at Walt Disney World.

In 1971, Marc Davis, one of Walt’s Nine Old Men said of Blair, “She was the most amazing colorist of all time. I don’t think even Matisse could hold a candle to her.”

Taking inspiration from The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries (1495–1505; also known as the Unicorn Tapestries) from The Met Cloisters, the exhibition demonstrates how Disney artist Eyvind Earle and his colleagues consulted them and other objects for the style of Sleeping Beauty.

Visitors will notice a number of colors that played a predominant role during the eighteenth century – particularly in paintings and ceramics – including blues, pinks, greens, and yellows. According to the Encyclopedia of Fine Arts, “several advances in colour chemistry had a major impact on the 18th-century colour palette” including Prussian Blue, Turner’s Yellow, and Cobalt Green. Madame Rose du Pompadour particularly favored pink and blue.

Materials and their Makers website states, “Rose Pompadour is the pink ground color invented by Sèvres in 1757, Madame de Pompadour … became a great supporter of the porcelain made at Sèvres, and it is in her honor that this color was named.”

In Sleeping Beauty, the colors blue and pink play a prominent role. Flora, one of the three good fairies, wants to make Aurora a dress for her 16th birthday and uses Merryweather as the model. As Flora finishes the pink dress, Merryweather, who wants it to be blue, changes it, irritating Flora who changes it back to pink. Merryweather changes it to blue again, and Flora changes it to pink; this continues, escalating, and becomes a magical quarrel over whether the dress should be pink or blue.

“Both Disney animated films and Rococo decorative works of art are infused with elements of playful storytelling, delight, and wonder,” said Max Hollein, Marina Kellen French Director of The Met. “Eighteenth-century craftspeople and 20th-century animators alike sought to ignite feelings of excitement, awe, and marvel in their respective audiences. Through exquisite objects and Disney artifacts, this exhibition will provide an unprecedented look at the impact of French art on Disney Studios productions from the 1930s to almost the present day.”

Wolf Burchard, the exhibition’s curator, added: “In mounting The Met’s first-ever exhibition devoted to Walt Disney and his studios’ oeuvre, it was important for us to explore his sources of inspiration as well as to recognize that his studio’s animated interpretations of European fairytales have become a lens through which many view Western art and culture today. Our fresh look on this material, which prompts an effervescent dialogue between the drawings and illustrations of some of the most talented artists in the Walt Disney Animation Studios and a rich array of the finest 18th-century furniture and porcelain, brings to life the humor, wit, and ingenuity of French Rococo decorative arts.”

In the next series of galleries, the exhibit jumps to the 1990s with Beauty and the Beast (1991). Originally, Walt wanted to adapt this 1740 tale by Suzanne-Gabrielle Barbot de Villeneuve (later a more widely known abridged adaptation -1756 – was written by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumontin) in the 1940s and ’50s.

“This expansive section will explore topics of anthropomorphism and zoomorphism in 18th-century French literature and decorative arts, Disney’s satirical take on Rococo fashion, the interiors of the movie’s enchanted castle, and the design and animation of the Beast and other characters.” Among the other art on display is a 16th-century portrait lent by Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, Austria, of Magdalena González, which has been associated with the story of Beauty and the Beast for generations.

“Preparatory movie sketches are shown alongside 18th-century clocks, candlesticks, and teapots (evoking the characters of Cogsworth, Lumiere, and Mrs. Potts from the movie) and illustrate the ways in which both Disney animators and Rococo craftspeople sought to breathe life into what is essentially inanimate. Highlights include a magnificent clock on a pedestal by André Charles Boulle, gilt-bronze candlesticks by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, and early Meissen teapots, including an anthropomorphic one of a bearded man riding a miniature dolphin, as well as a pair of Sèvres elephant vases designed by Jean-Claude Chambellan Duplessis.” It is easy to see Cogsworth and Lumiere in these two items.

Photo by Paul Lachenauer, Courtesy of The Met. © Disney

The exhibit explains the Beast’s transformation scene, which was animated by Glen Keane, and inspired by sculptor Auguste Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais. It also shows how the ballroom scene drew on the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and concludes with a Be Our Guest-inspired display that shows how polished silver and porcelain buffets were part of the festivities at Versailles and other European courts.

“The concluding section examines Disney architecture, specifically the fairytale castles that are central focal points in many Disney movies and theme parks.” In the parks, these castles are known as “weenies.” “While the fantastical buildings exist outside actual periods and styles, Disney’s artists were heavily influenced by French and German architecture when creating their settings, particularly for amusement parks. A presentation of Walt Disney Imagineering concept art illustrates these Disney architectural designs and historical comparisons—such as the 16th-century Loire Valley chateaux and the 19th-century Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria.”

In what could be considered the exhibit’s “weenie,” is Herb Ryman’s drawing of Disneyland. This detailed map, under Walt’s guidance, was drawn over one weekend in the fall of 1953. The following week, a final, hand-colored version of this map was taken to New York City by Walt’s brother, Roy Disney, as his main presentation piece in order to get the financing needed to build Disneyland.

Also on display are two pair of “so-called” Tower vases, made by Sèvres around 1762–63 and are reunited for likely the first time in history. One pair is green and the other is pink. “I remember looking at the pink one for the first time, thinking, ‘Gosh, that looks just like a Disney castle,’” says Burchard. “In a way, what we have here is the same rhetoric we find in the Disney castle. It’s really an architecture of the imagination.”

The exhibit is spectacular. In Disney history and previous exhibits, reference items were sometimes touched upon, but previous exhibits never really showed the actual objects that Disney and his animators drew inspiration from for their films and parks. This exhibit gives such detailed context and a deeper understanding of Disney’s classic films. It makes it easy for visitors to connect the dots and arrive at that “ah-ha” moment. “Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts” has now become the gold standard by which every future Disney exhibit should be judged.

The exhibition will be featured on The Met website as well as on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter using the hashtag #InspiringWaltDisney.

Featured image: @DisneyAnimation